Shovel Point, Tetagouche State Park, Illgen City, MinnesotaHuman Evolution

Modern day humans, Homo sapiens, are an upright-walking species that lives on the ground and very likely first evolved in Africa about 315,000 years ago. Homo sapiens is the only existing living member of what zoologists refer to as the human tribe, Hominini. There is abundant fossil evidence to indicate that humans were preceded for millions of years by other primate-like hominins, such as Ardipithecus, Australopithecus, and other species of Homo, and that our species also lived for a time contemporaneously with at least one other member of our genus, Homo neanderthalensis (the Neanderthals). In addition, human predecessors have always shared Earth with other apelike primates, from the modern-day gorilla to the long-extinct Dryopithecus (giant ape). That humans are related to apes, both living and extinct, is accepted by anthropologists and biologists everywhere.

The exact nature of our evolutionary relationships has been the subject of debate and investigation since the great British naturalist Charles Darwin published his monumental books On the Origin of Species (1859) and The Descent of Man (1871). Darwin never claimed, as some of his Victorian contemporaries insisted, that “man was descended from the apes,” and modern scientists would view such a statement as a useless simplification—just as they would dismiss any popular notions that a certain extinct species is the “missing link” between humans and the apes. There is theoretically, however, a common ancestor that existed millions of years ago. This ancestral species does not constitute a “missing link” along a lineage, but rather, a divergence into separate lineages. This ancient primate has not been identified and may never be known with certainty, because fossil relationships are unclear even within the human lineage, which is more recent. In fact, the human “family tree” may be better described as a “family bush,” within which it is impossible to connect a full chronological series of species, leading to Homo sapiens.

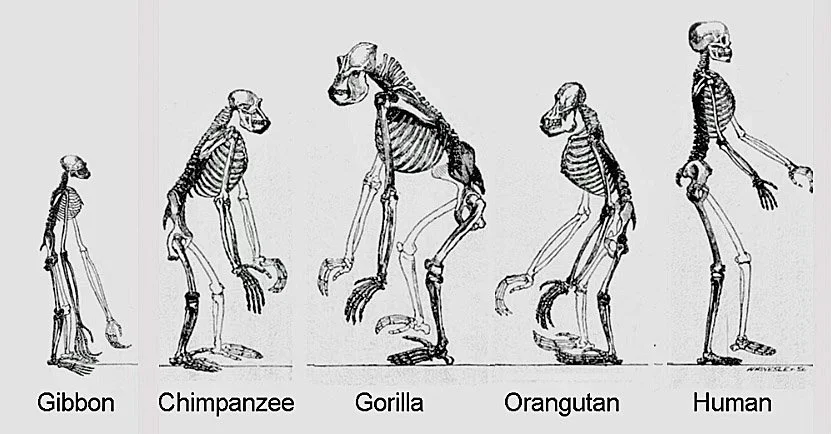

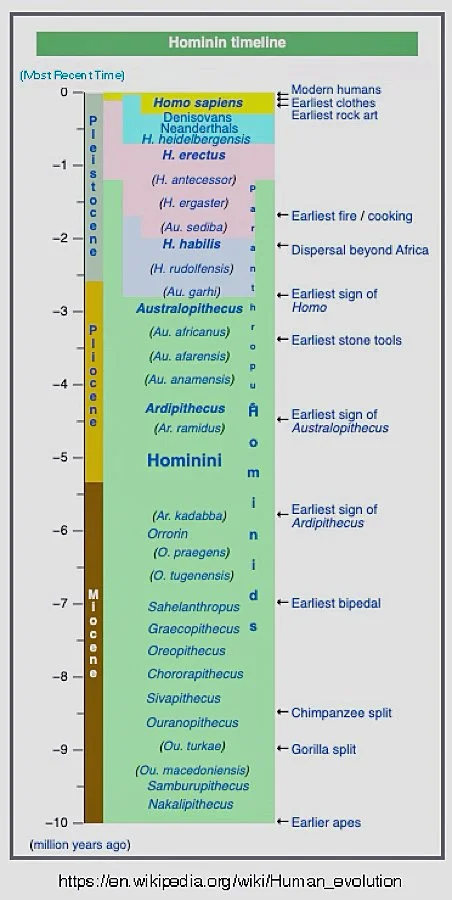

Primates diverged from other mammals about 85 million years ago (Mya), in the Late Cretaceous period, with their earliest fossils appearing over 55 Mya, during the Paleocene. Primates produced successive clans leading to the ape superfamily, which gave rise to the hominid and the gibbon families; these diverged some 15–20 Mya. African and Asian hominids (including orangutans) diverged about 14 Mya. Hominins (including the Australopithecine and Panina subtribes) parted from the Gorillini tribe between 8 and 9 Mya;

Australopithecine (including the extinct biped ancestors of humans) separated from the Pan genus (containing chimpanzees and bonobos) 4–7 mya. The Homo genus is evidenced by the appearance of Homo habilis over 2 Mya. Anatomically erect modern humans emerged in Africa approximately 300,000 years ago.

Over their evolutionary history, humans gradually developed traits such as bipedalism, dexterity, and complex language, as well as interbreeding with other hominins, indicating that human evolution was not linear but weblike. The study of the origins of humans involves several scientific disciplines, including physical and evolutionary anthropology, paleontology, and genetics; the field is also known by the terms anthropogeny, anthropogenesis, and anthropogony.

One of the oldest known primate-like mammal species, Plesiadapis, came from North America; another, Archicebus (forest dweller), came from China. Other such early primates include Altiatlasius and Algeripithecus, which were found in Northern Africa. Other similar basal primates were widespread in Eurasia and Africa during the tropical conditions of the Paleocene and Eocene.

Evolution of Homini

Among the numerous predecessor of Hominini, the genus Australopithecus is possibly the most extensively studied. Australopithecus evolved in eastern Africa around 4 million years ago before spreading throughout the continent and eventually becoming extinct 2 Mya. Australopithecus existed as numerous species. Australopithecus prometheus, otherwise known as Little Foot, has recently been dated at 3.67 Mya. Given the opposable big toe found on Little Foot, it seems that the specimen was a good climber. It is thought given the night predators of the region that he built a nesting platform at night in the trees in a similar fashion to chimpanzees and gorillas.

The earliest documented representative of the genus Homo is the Ledi jaw, which is dated 2.75 - 2.8 million years ago (Mya), and is the earliest species for which there is positive evidence of the use of stone tools. The brains of these early Hominins were about the same size as that of a chimpanzee, although it has been suggested that this was the time in which the human SRGAP2 gene doubled, producing a more rapid wiring of the frontal cortex. During the next million years a process of rapid encephalization occurred, and with the arrival of Homo erectus and Homo ergaster in the fossil record, cranial capacity had doubled to 850 cm3. Such an increase in human brain size is equivalent to each generation having 125,000 more neurons than their parents. It is believed that Homo erectus and Homo ergaster were the first to use fire and complex tools, and they were the first of the Hominini to leave Africa, spreading throughout Africa, Asia, and Europe between 1.3 to 1.8 Mya. A hypothesized Hominini timeline during the Middle Paleolithic is presented below; The horizontal axis represents geographic location; the vertical axis represents time in millions of years ago (Mya).

Modern Humans

Homo erectus spread across Eurasia starting around 1.8 Mya. Homo heidelbergensis is believed to diverge into Denisovans (precursors to Neanderthals), Neanderthals, and Homo sapiens. With the expansion of Homo sapiens after 0.2 Mya, Denisovans, Neanderthals, and unspecified archaic African hominini are thought to have been subsumed into the H. sapiens lineage.

Admixture events in modern African populations are also indicated. One of the species of Homo heidelbergensis, Homo rhodesiensis, or Homo antecessor are believed to have migrated out of the continental Africa 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, gradually replacing local populations of Homo erectus, Homo floresiensis, and Homo luzonensis, whose ancestors had left Africa in earlier migrations.

Archaic Homo sapiens, the forerunner of anatomically modern humans, evolved in the Middle Paleolithic between 400,000 and 250,000 years ago. Recent DNA evidence suggests that several haplotypes of Neanderthal origin are present among all non-African populations, and other hominini, such as Denisovans (predecessors to Neanderthal), may have contributed up to 6% of their genome to present-day Homo sapiens, suggestive of interbreeding between these species. According to some anthropologists, the transition to behavioral modernity with the development of symbolic culture, language, and specialized lithic technology happened around 50,000 years ago (beginning of the Upper Paleolithic), although others point to evidence of a gradual change over a longer time span during the Middle Paleolithic. Homo sapiens is the only currently extant species of its genus, Homo. While some (extinct) Homo species might have been ancestors of Homo sapiens, many, perhaps most, were likely "cousins", having speciated away from the ancestral hominini line.

The Sahara pump theory (describing an occasionally passable "wet" Sahara desert) provides one possible explanation for the intermittent migration and speciation in the genus Homo. Based on archaeological and paleontological evidence, it has been possible to infer, to some extent, that ancient dietary practices of various Homo species and the role of diet in physical and behavioral evolution occurred within Homo.

Some anthropologists and archaeologists subscribe to the Toba catastrophe theory, which posits that the supereruption of Lake Toba on Sumatra in Indonesia some 70,000 years ago caused global starvation, killing the majority of humans and creating a population bottleneck that affected the genetic inheritance of all humans today. The genetic and archaeological evidence for this remains in question however.

A 2023 genetic study suggests that a similar human population bottleneck of between 1,000 and 100,000 survivors occurred "around 930,000 and 813,000 years ago. That lasted for about 117,000 years and brought human ancestors close to extinction.

Neanderthal

Homo neanderthalensis, alternatively designated as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, lived in Europe and Asia from 400,000 to about 28,000 years ago. There are a number of clear anatomical differences between anatomically modern humans and Neanderthal specimens, many relating to the superior Neanderthal adaptation to cold environments. Neanderthal surface to volume ratio was even lower than that among modern Inuit populations, indicating superior retention of body heat. Neanderthals also had significantly larger brains, as shown from brain endocasts, casting doubt on their intellectual inferiority to modern humans. However, the higher body mass of Neanderthals may have required larger brain mass for body control. Recent research has shown important differences in brain architecture. The larger size of the Neanderthal orbital chamber and occipital lobe suggests that they had a better visual acuity than modern humans, useful in the dimmer light of glacial Europe.

Neanderthals may have had less brain capacity available for social functions. Inferring social group size from endocranial volume (minus occipital lobe size) suggests that Neanderthal groups may have been limited to 120 individuals, compared to 144 possible relationships for modern humans. Larger social groups could imply that modern humans had less risk of inbreeding within their clan, trade over larger areas (confirmed in the distribution of stone tools), and faster spread of social and technological innovations. All these may have contributed to modern Homo sapiens replacing Neanderthal populations by 28,000 years. Earlier evidence from sequencing mitochondrial DNA suggested that no significant gene flow occurred between Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens, and that the two were separate species that shared a common ancestor about 660,000 years ago. However, a sequencing of the Neanderthal genome in 2010 indicated that Neanderthals did indeed interbreed with anatomically modern humans c. 45,000-80,000 years ago, around the time modern Homo sapiens migrated out from Africa, but before they dispersed throughout Europe, Asia and elsewhere. The genetic sequencing of a 40,000-year-old Homo sapiens skeleton from Romania showed that 11% of its genome was Neanderthal, implying the individual had a Neanderthal ancestor 4–6 generations previously, in addition to a contribution from earlier interbreeding in the Middle East. Though this interbred Romanian population seems not to have been ancestral to modern humans, the finding indicates that interbreeding happened repeatedly.

Reference:

Human evolution | History, Stages, Timeline, Tree, Chart, & Facts | Britannica 2025

Human Evolution_Wikipedia 2025

Human Evolution | Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History 2025